Introduction

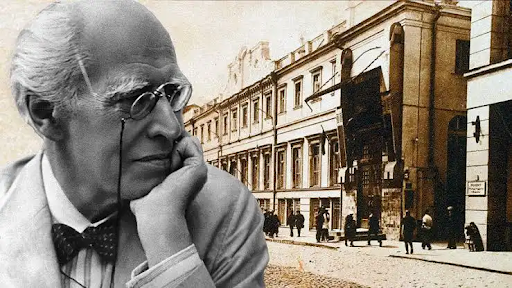

Few names resonate more in the history of acting than Konstantin Stanislavski. His system of training revolutionized how performers approached their craft, moving away from exaggerated gestures and declamation toward psychological realism. What made his approach groundbreaking was the focus on inner truth—actors living the role rather than simply performing it.

One of the most influential aspects of his work lies in his emotional techniques. These methods help actors generate genuine emotional experiences that audiences can feel. By relying on memory, imagination, and the “given circumstances” of the story, Stanislavski’s techniques enable actors to create believable characters across different roles.

This article will unpack how Stanislavski’s emotional techniques work, why they remain foundational to modern acting, and how they convert into performances that audiences trust.

1. Understanding Stanislavski’s System

Before exploring his emotional techniques, it is important to understand the broader framework of Stanislavski’s system. Developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, his system emphasized:

- The “Magic If”: Actors ask, “What if I were in this situation?” This encourages empathy and imagination.

- Given Circumstances: Every detail of the play’s world—time, place, relationships, events—shapes the actor’s approach.

- Objectives and Super-objectives: Characters must have clear goals driving their actions.

- Emotional Truth: Instead of pretending to feel, actors strive to genuinely experience emotions within the fictional context.

Within this system, emotional techniques play a vital role.

2. Emotional Memory and Its Application

One of Stanislavski’s most famous concepts is emotional memory (sometimes called affective memory). The idea is simple: actors recall real past experiences that mirror the emotional tone of the scene they are performing.

Example:

If an actor must portray grief over losing a loved one, they might recall the loss of a pet, the end of a relationship, or a moment of profound disappointment. By tapping into their own experiences, the performance becomes infused with real emotion.

Benefits:

- Creates authenticity that audiences recognize.

- Helps actors access emotions they may not otherwise feel in the moment.

Challenges:

- Overuse can lead to emotional exhaustion.

- Risk of blurring personal trauma with fictional performance.

Many later teachers, such as Lee Strasberg in Method Acting, expanded this technique, though Stanislavski himself eventually emphasized imagination as a safer tool.

3. Imagination and the “Magic If”

While emotional memory taps into personal history, imagination broadens the possibilities. The “Magic If” asks actors to place themselves inside the fictional world. For example, “What if I were a soldier facing battle?” Even if the actor has no personal experience of war, imagination bridges the gap.

Imagination allows actors to:

- Create emotional truth without relying solely on personal memory.

- Explore roles beyond their own lived experience.

- Build empathy by envisioning life from another perspective.

Stanislavski emphasized that the actor’s imagination must be detailed and specific. The more vividly one envisions the circumstances, the more authentic the performance becomes.

4. The Role of Given Circumstances

Emotions are not expressed in isolation; they arise within context. Stanislavski urged actors to analyze the script thoroughly to understand the given circumstances—the details that shape a character’s reality.

For example:

- A character’s social class affects how they express anger or joy.

- The historical setting influences vocabulary, gestures, and expectations.

- Relationships with other characters determine emotional tone.

By grounding emotions in the given circumstances, performances gain believability and coherence.

5. The Objective and Emotional Drive

Characters always pursue something. This pursuit—their objective—is the engine of action and emotion. Stanislavski encouraged actors to break down a role into smaller objectives (scene goals) and connect them to the character’s super-objective (the overarching desire).

Emotions naturally arise from pursuing objectives. For example, if a character’s super-objective is love, every interaction will be charged with emotional stakes related to gaining or losing it. Actors who focus on objectives avoid “playing emotions” directly; instead, they let emotions emerge organically from pursuit.

6. The Circle of Attention

To maintain authenticity, Stanislavski taught actors to manage their circle of attention—their focus onstage. Narrowing attention to immediate surroundings helps actors stay grounded in the moment, preventing self-consciousness.

This focus enhances emotional truth because it keeps actors engaged in the reality of the scene rather than distracted by the presence of an audience.

7. The Physical Actions Approach

In his later years, Stanislavski emphasized physical actions as the gateway to emotion. By committing to specific, purposeful actions, actors trigger genuine emotional responses.

For example, gripping a photograph of a lost loved one tightly while speaking about them may evoke real grief. Physical actions ground emotions in the body, making them repeatable and reliable.

This method solved a key challenge: emotional memory was unpredictable, but physical actions provided a concrete entry point into emotion.

8. Believability Through Ensemble Work

Stanislavski stressed that no actor exists in isolation. Emotional truth emerges from genuine interaction with fellow actors. Techniques such as listening, reacting, and ensemble rehearsals help build chemistry.

Believability is enhanced when actors allow themselves to be emotionally affected by others onstage, creating dynamic and spontaneous performances.

9. Influence on Modern Acting

Stanislavski’s emotional techniques shaped nearly every acting tradition that followed. From Method Acting in the United States to Meisner’s focus on repetition and presence, his ideas echo across theatre and film.

Modern actors often blend his techniques with others. For example:

- Daniel Day-Lewis has been known to immerse himself fully in given circumstances, living as his character even off set.

- Meryl Streep often emphasizes objectives and given circumstances to find emotional truth without relying on personal trauma.

The durability of Stanislavski’s approach lies in its adaptability.

10. Case Study: Emotional Truth on Screen

Consider Manchester by the Sea (2016). Casey Affleck’s performance was praised for its raw emotional authenticity. While not a direct student of Stanislavski, his process reflects the system: careful analysis of circumstances, attention to objectives, and emotional availability through imagination and memory.

Such performances show how Stanislavski’s emotional techniques remain timeless.

11. Challenges and Misinterpretations

Some misinterpretations of Stanislavski’s work have caused controversy. For instance, Strasberg’s emphasis on emotional memory led some actors to overindulge in personal trauma, a practice Stanislavski later cautioned against.

The key is balance: using memory, imagination, and physical action together to achieve emotional truth without harm.

12. Practical Exercises

Actors can train in Stanislavski’s emotional techniques through exercises such as:

- Emotion Recall Journaling: Writing down past emotional experiences and practicing accessing them.

- Imagination Expansion: Creating detailed sensory images of fictional scenarios.

- Objective Mapping: Breaking down a script into objectives and super-objectives.

- Physical Action Rehearsals: Performing tasks with emotional focus, such as packing a suitcase in anger.

These exercises keep the actor’s emotional muscles flexible and reliable.

Conclusion

Stanislavski’s emotional techniques revolutionized acting by grounding performances in truth rather than artifice. By drawing on emotional memory, imagination, given circumstances, objectives, and physical actions, actors convert scripts into believable human experiences.

Believability is not about faking feelings but about living them authentically within the story. This is why Stanislavski’s legacy continues to shape actors worldwide, from stage to screen. His system offers not just tools for performance but also a philosophy: that acting, at its best, is a profound exploration of human truth.